For those who have been following me here for a while, you’ll know that we’ve come to the time at the end of the year where I share the highlights from my reading for the year. It’s been a diverse year again, with some excellent new books as well as some classics I’ve only just discovered. Unsurprisingly, the genre I read most of was once again poetry, but it was also an excellent year for graphic novels and non-fiction. So here are the five best in five categories.

Novels

1. Wandering Stars – Tommy Orange

Longlisted for the 2024 Booker Prize but not making the shortlist, this was the first novel by an American First Nations author to be nominated. Why it was culled in preference for some much less impressive novels has left many baffled. Orange’s novel tells the story of a Cheyenne family from a massacre that begins the saga of familial trauma through to the present day, finishing with the children and women who must learn how to live with the wounds of the past. Unflinching and yet ultimately hopeful, the novel tells the story of the America that few are willing to confront but need to do so for the country to heal.

2. Headshot – Rita Bullwinkel

Another excellent novel to be Booker longlisted but not shortlisted, “Headshot” is not a book that I expected to love. Chronicling the two days of a young women’s boxing tournament, the novel moves through each round of the tournament, moving between the matches and the characters’ pasts and futures, the chapter titles revealing who progresses to the next match with only the ultimate winner left hidden until the final pages. Both intimate and ultimately cosmic in scale (I won’t reveal how that happens; no spoilers!), this novel managed to engross me in a sport in which I have no interest at all and drew me into the lives of its disparate protagonists who, in very little time and with Bullwinkel making no effort to glamorise them, each managed to win my attention and sympathy.

3. The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood

I should probably have read this years ago, but the TV show, which I never managed to finish, put me off. The novel, I was pleased to discover, was much subtler, and went for a brooding disquiet where the series opted for shock and grotesqueness. Profoundly uncomfortable to read as a man yet compelling for the same reason, this novel opened my eyes to male privilege in a way that both sent me reeling and hungry to learn more.

4. The Edge of the Alphabet – Janet Frame

Reading Janet Frame feels a little like seeing where Katherine Mansfield might have taken New Zealand literature if she had lived longer. This modernist classic was republished by Fitzcaraldo for the centenary of Frame’s birth and it tells the story of three strangers brought together on a boat from New Zealand to England. The most powerful and moving of the characters is a teacher in her thirties moving home to England. Her story is tragic but told with extraordinary pathos and with remarkable honesty for its day about a woman’s sexual frustration. Frame is a hard but rewarding and transfixing read.

5. Beloved – Toni Morrison

Another classic I should have read earlier, this was perhaps one of the most harrowing reads of the year for me. I entered it knowing nothing about it except that it dealt with slavery. I will spoil nothing for readers who don’t know it’s secret, but be prepared to be taken into a world of grief, trauma, and the lengths humans can be driven to when systematically dehumanised. And marvel at how Morrison somehow manages to bring healing into such tragedy.

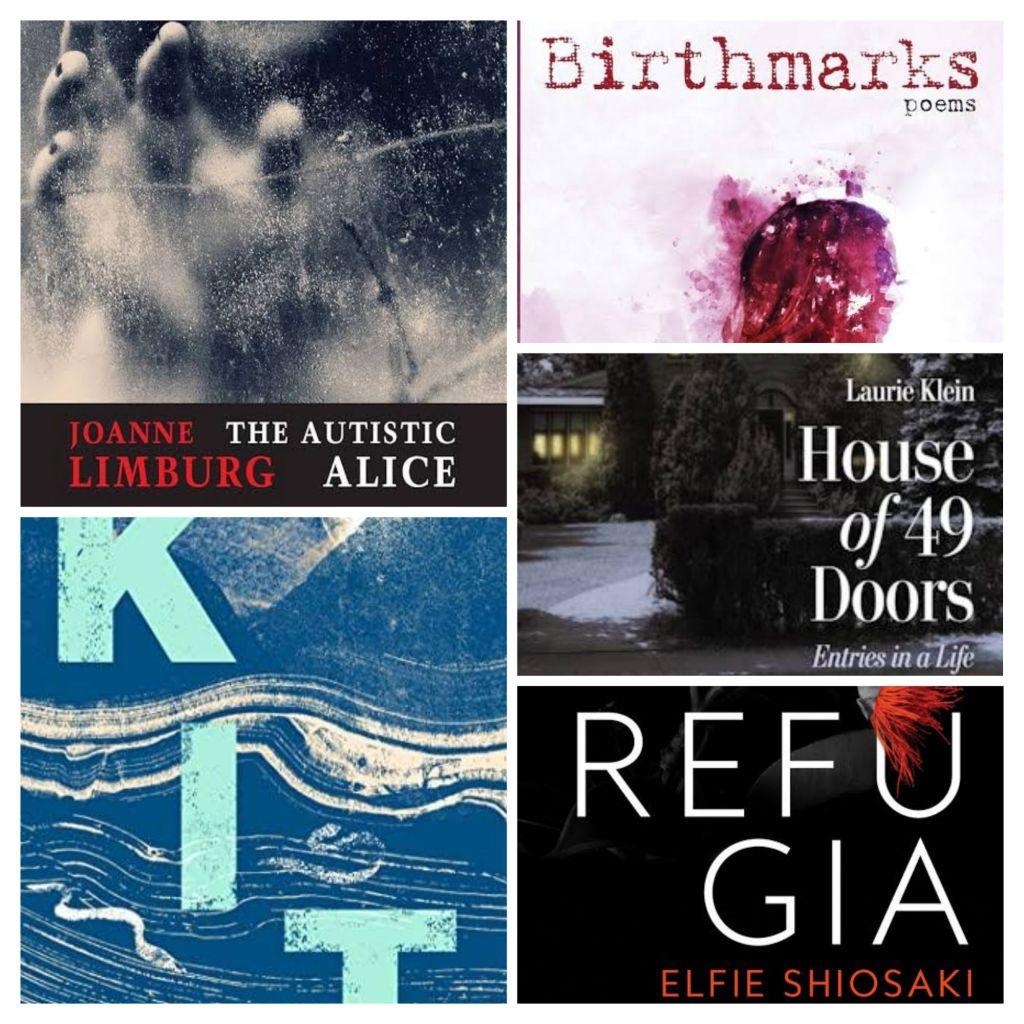

Poetry

1. Birthmarks – Whitney Rio-Ross

This wonderful chapbook was one of my favourite discoveries of the year. Rio-Ross takes the reader through the untold or neglected stories of women throughout the Bible, sometimes imagining them in contemporary settings (a childless woman at a baby shower), always bringing new light and grace to these fundamental stories of faith.

2. House of 49 Doors – Laurie Klein

I had the pleasure of reading an early copy of this for an article I wrote for Amethyst Review on Klein’s poetry. I adored her first book, “Where the Sky Opens”, and was equally amazed by her latest, exploring the trauma of her beloved uncle’s death when Klein was a child. A tender and healing work.

3. Kit – Megan Barker

Difficulty to categorise, Barker’s debut is most like the verse-infused novels of Max Porter, but sits more comfortably in poetry than Porter does. A tender and harrowing tale of a friend’s depression and ultimate death, Barker manages to be unflinching while also sensitive. Content warning of suicide themes, but handled with remarkable tact.

4. Refugia – Elfie Shiosaki

Shiosaki’s debut was one of my favourite books of Australian poetry. In her follow-up, she continues to explore archival and historical documents, this time about the settlement of Perth and the attempts to displace the Noongar people. Shiosaki’s work sends the resounding message that the Noongar people are still here, and growing stronger. A work that manages to be confronting and uplifting at once.

5. The Autistic Alice – Joanne Limburg

Limburg blends the tropes of Lewis Carroll’s work with autobiographical accounts, dealing with familial trauma, misunderstanding and grief, in a way that brings to life the inner world of an autistic person, with soul and insight.

Short Fiction

1. Stories of Your Life & Others – Ted Chiang

Like many people, I first came across Ted Chiang’s short stories through the film “Arrival”, which adapted his “Stories of Your Life”. This year I finally read the whole collection it comes from and was entranced. Chiang’s intelligence is formidable and I often found myself needing to be an expert in a variety of topics from Kabbalah to pure mathematics. Some of the stories have not dated so well, such as the final story which describes a world in which people can be given technological implants to prevent them from seeing the attractiveness of another person – an amazing concept but full of gender roles that sit awkwardly in today’s society. That said, Chiang is a versatile stylist and intellect and his stories are always entry points to fascinating and illuminating worlds.

2. Public Library – Ali Smith

This collection seems to have been birthed out of some austere government policy in the UK leading to mass closures of public libraries. Each story deals with the role of libraries and books in its character’s lives and is interspersed with accounts from the British public about their memories of libraries. An often tender and inspiring celebration of the power of reading and the importance of human access to books.

3. Only the Astronauts – Ceridwen Dovey

Dovey’s first collection of stories, “Only the Animals”, took the perspective of a variety of animals, most of them connected to famous authors. It was an intriguing and often entertaining concept, though sometimes the conceipt didn’t wholly come off. Her latest collection runs a similar risk, with each story this time being told from the perspective of space junk, and not all the inanimate narrators feel credible. But the concept is so endearing and so often used to highlight some human folly or evil, that it almost always works. The oddest story is from the perspective of one of the hundred tampons that male engineers thought the first American female astronaut would need on her one week space mission (they never asked her how many she needed; she was not even on her period at the time). Tampons are hard to anthropomorphise, and the story is longer than it needs to be, but it opened up such a horrifying and instructive moment in history that I was grateful to read it. The best stories are the ones where humanity is credibly explored through non-human means, which Dovey almost always manages to do.

4. The Garden Party and Other Stories – Katherine Mansfield

When Mansfield died in her 30s from tuberculosis, her rival Virginia Woolf expressed grief that history would never know for sure which of them was the greater writer. I love both writers, but it’s hard to beat the subtlety and intensity of Mansfield’s short stories. Whether evoking the rural New Zealand of her childhood or the 1920s Europe she adopted as her adult home, Mansfield’s stories are full of humanity, unanswered questions and thwarted epiphanies. I wish we could have seen what more years would have brought to her craft.

5. Green Frog – Gina Chung

A lot of the contemporary short fiction I read runs the risk of becoming gimmicky. The concepts that Chung employs in her debut collection – tech that allows parents to have AI versions of their deceased children; a story from the perspective of a praying mantis – could be gimmicky in less skilled hands. But Chung is deft in how she executes her stories and she always employs the powers of silence and suggestion that are central to the form to great effect. Her stories are always skillful, often disturbing, and consistently rewarding.

Graphic novels and comics

1. The Reddest Rose: Romantic Love from the Ancient Greeks to Reality TV – Liv Strömquist

I love a graphic novel that incorporates social theory and philosophy. Strömquist is probably one of the smartest and most engaging artists working in the form at the moment, and though she isn’t for the faint-hearted (especially her other work, “The Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs the Patriarchy”), she is surprisingly funny and winsome. This book takes the reader through a history of how romantic love has been understood over the ages, arriving at a conclusion that, though not framed in Christian terms, fits perfectly with a Christian understanding of love as sacrifice.

2. The Mental Load: A Feminist Comic – Emma

French feminist comic artist Emma has a very simple, almost childlike style of drawing that allows her to capture complex, gritty and sometimes dark ideas in a surprisingly winsome way. The title chapter in this collection dramatically changed how I saw the distribution of parenting work between genders and all the hidden assumptions that underlie how men often think of parenting and paid work compared to women. Other chapters tackle incidental misogyny (like the regular sexism she experienced as a younger woman working in hospitality, including customers feeling entitled to say, “I can see your panty lines; you should be wearing a G-string”) through to more complex systemic issues including police violence. Sometimes funny, often heartbreaking, always illuminating, I can’t think of many books that impacted me more this year than this one.

3. The Tenderness of Stones – Marion Fayolle

One of the most visually beautiful and intriguing graphic novels I’ve read. A surrealist allegory about a family coping with grief, the story is told through powerful imagery that seems to contradict itself at first, but slowly reveals its meaning with subtle and lasting impact.

4. Medea – Blandine Le Callet and Nancy Peña

I first discovered the story of Medea, the slighted Barbarian wife of famed Argonaut Jason – when I was in high school, reading it in Euripides’ seminal account. This feminist retelling starts with Medea as a child and follows through to her death as an unimaginably old woman. Making the fantastical elements of the story more realistic – Medea’s witchcraft, for instance, is reimagined as a kind of alchemy or folk medicine – the novel also seeks to rehabilitate Medea without excusing her more brutal actions. The rendering is not without its flaws. Medea’s frequent nudity tends to emphasise her beauty rather than the freedom it is supposed to represent; though her body is briefly allowed to change when she is pregnant, she returns to her lithe form quickly, and the ageing Medea later on feels no need for the nude beach evenings that are a frequent part of the rest of her life. But the story unfolds skillfully and her character is generally rendered with subtlety and sympathy. A fascinating take on a classic tale.

5. Jane, the Fox & Me – Fanny Britt and Isabelle Arsenault**

There is a lot of wonderful art coming out of French Canada at the moment. This gem from Montreal was hidden away in the Junior Graphic Novels section of my local library but something told me it might have appeal to adults. I wasn’t disappointed. It tells the story of a young misfit who has become the object of cruel bullying by her former friendship group and finds solace in reading “Jane Eyre”. Her own story is told in black and white and Jane’s in colour, until their stories begin to merge and the narrator finds friendship and belonging. Exquisite and vivid illustration perfectly complements this tender and beautifully developed tale of adolescence.

Non-fiction

1. Reading While Black – Esau McCaulley

It’s hard to seperate this, McCaulley’s first book on African American biblical interpretation, from his memoir, “How Far to the Promised Land”. Both are full of personal accounts of growing up African American in the twentieth century and how his experiences shaped his understanding of scripture. This was one of the most formative books for me in showing how my cultural experiences have limited my ability to see the richness of the Bible. McCaulley is also deft at dealing with complex and thorny issues in Biblical interpretation, maintaining orthodoxy while also highlighting how cultural biases can rob our orthodoxy of the full richness of God’s biblical witness.

2. Pulling the Chariot of the Sun – Shane McCrae

I discovered McCrae’s poetry a few years ago, and books by him have featured in this list a number of times. His memoir tells in full the story that he often alludes to in his poetry – of being kidnapped from his white mother and kept from meeting his black father by his white supremacist grandfather. McCrae’s poetry is dense and so is his prose, but he explores the subjectivity of memory and the trickery that trauma plays on the mind to great effect, arriving at what is ultimately a healing and uplifting conclusion.

3. The White Book – Han Kang

Many of my readers might know that I have a tradition of always reading the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. I was a little apprehensive about reading Kang’s novels but could bring myself to read this symbolic memoir that begins as a list of white things and becomes an exploration of grief and memory. A powerful and beautiful work that makes me think I might try some more of her books.

4. A Woman’s Story – Annie Ernaux

I read Ernaux’s first book about her mother, “I Remain in Darkness”, when she won the Nobel two years ago. Though I appreciated it, it didn’t amaze me. But this slim work, written after her mother’s death and seeking to recover her mother’s life, is tender, honest and powerful: able to hold together great love for her mother with unflinching recognition of her weaknesses. What emerges is intensely personal and ultimately a moving tribute to what many women have had to overcome.

5. Good and Beautiful and Kind – Rich Villodas

New York pastor Rich Villodas’ first book, “The Deeply Formed Life”, was a life changing read for me a couple of years ago. I was very excited to discover he had written a new book, though this one was often slow going for me, being so dense with spirituality weighty things that it took a long time to digest. But this is a book that many people in our world need to read. How can we overcome the increasing fractures in our society, especially in the evangelical church? At its heart this book is a celebration of the goodness, beauty and kindness of the Gospel.