When I was in Year 7, we were required to read thirty books as part of a “general reading” assessment in English. Each week we would go to the library, log the books we had read, and either our teacher or the librarian would quiz us on the books to confirm we had read them. Although I had been a voracious reader when I was younger, I remember finding reading hard at that time. My appetite was for books that were more mature than I was and I bored easily. But my family also made fun of me forever changing books so I developed a strategy of simply claiming to have finished a book when I hadn’t. Occasionally a book would grab my attention for long enough that I would hyperfocus on it and devour it until it was gone. But mostly this was rare, and would be until I reached an age when the books that matched my reading level also matched my emotional development.

So in year 7 I fudged my way through the year of general reading, logging books I had barely skimmed, and trading on the trust my teachers had in me as a “good student” to make it through the cursory questions I received on my reading. Most of the time I logged so many books that they couldn’t be bothered quizzing me. When they professed amazement at my rate of reading, I probably seemed modest, but really I was embarrassed. I didn’t want the attention. I just wanted to be left alone.

This year I started using a new app to log my reading, and at any given moment I have around ten books or more listed as “currently reading”. Most of the time I have at least one novel, one book of poetry and one or more devotional or theological books on the go. When I say that I read 160 books this year, I need to assure you that, unlike my 12-year-old self, I’m telling the truth. But many were poetry books (meaning, short), a few were graphic novels, and lots were novellas (meaning, short). My attention still wanes easily, though now I have a diagnosis to explain that. But I am constantly in a book; I’ve just learnt how to move between the vicissitudes of my fickle attention span.

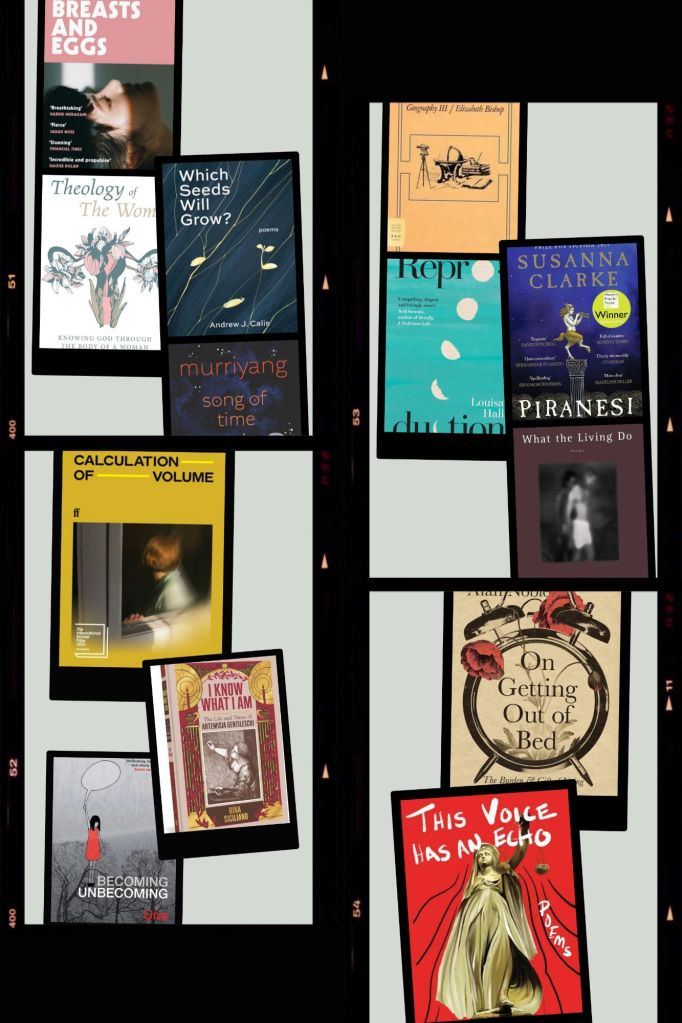

I consumed so much poetry this year that it’s hard to single out the highlights. Some I remember loving profoundly when I first read them but can’t tell you now why. But my journey through the complete Elizabeth Bishop at the start of the year has stayed with me, especially Geography III, which features many of her most famous poems and is Bishop at her most formally complex and dextrous. Her friend and mentor Marianne Moore also brought me almost to tears with the beauty of some of her lines in What Are Years? In new poetry, I discovered Palestinian-American poet Andrew Calis when he reviewed my latest book for Fare Forward. Reading Which Seeds Will Grow? felt like meeting a new friend: tender and grounded in the grace of everyday things while also soaring, cosmic and sublime. I will return often to his work, and am grateful to have had it enter my life. Likewise, but in a very different vein, was Emma McCoy’s This Voice Has An Echo, a marvellous collection of Midrash-like poems on Old Testament prophets. McCoy is a Christian poet who isn’t afraid to make her prophets swear and does not varnish over the messiness of life but manages to develop a voice that echoes with grace and hope. I was late to the party with Marie Howe, but her Pulitzer-winning collection this year made me go back and discover her older work. What the Living Do, which primarily concerns her brother’s death with AIDS but also wrestles with gender and the world that women grow up into, is raw, visceral and transcendent. I had a similar feeling reading Michael Kleber-Diggs’ Worldly Things, a tender and vulnerable portrayal of fatherhood and of growing up black in America.

In fiction, I struggled to keep up with a lot of the major literary prizes this year like I normally would, but it was a great year for the International Booker. The winner, Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq, is well worth the read, though I must admit I found it difficult: the distinctiveness of its cultural voice, reflecting a side to Indian culture not often read about (Muslim women of Southern India, written originally in Kannada, with some Urdu and Arabic), also made it very unfamiliar and sometimes alienating to me. But I enjoyed seeing a collection of short stories win a major award and the collection gives voice to women’s perspectives in a context where they might not often be heard. Other nominees stood out to me more. I reviewed Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection for Fare Forward, so you can read my thoughts on it in more detail here, and my review of the first three parts to Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume when it comes out in Fare Forward’s newsletter in the new year. I also discovered some contemporary classics that I’ve missed previously. Alias Grace showed me that my unexpected love of The Handmaid’s Tale was not an anomaly; I think I actually like Margaret Atwood. She is sometimes austere, always challenging, but surprisingly tender and humane. And Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, which I initially thought might be overhyped, was every bit as complex and beautiful as I’d been told it is. I also found myself delving into lots of books about women’s struggles with fertility and other aspects of being in their bodies: Mieko Kawakami’s Breasts and Eggs was a rich and engrossing story of two sisters, one planning a breast enhancement operation, the other exploring the complex and often unregulated world of sperm donation. Louisa Hall’s Reproduction was a much darker work, blending accounts of Mary Shelley’s life and work with the vivid, often confronting story of the narrator’s experiences of childbirth and miscarriage. It verges at times on body horror but in a way that remains grounded in the realities of life, and it shocks not to horrify or disgust but to help us understand and connect. I was also entranced by Ali Smith’s unnervingly realistic dystopia Gliff and its subtle and quietly chilling exploration of the boundaries between survival and compliance. In short fiction, I was spellbound by Pippa Goldschmidt’s Schrodinger’s Wife, a collection of stories of forgotten and marginalised women in science which opened my world to women who should be much more famous than they are, including Lise Meitner who is now a key player in the new collection of poems I’m working on.

There were not many non-fiction standouts in my reading this year, but Christy Angelle Bauman’s Theology of the Womb was an incredible read. It begins with the question: if women are made in the image of God as much as men are, then what can we learn about God from the experiences that women have in their bodies? From there it becomes one of the most comprehensive theological reflections on female embodiment that I’ve encountered, going even further than A Brief Theology of Periods, which I was already amazed by (and included in this list in 2022). It’s a rare theology book that can deal with as much pastoral nuance and spiritual depth with menstruation, lactation, clitoral orgasms and mastectomies, and it is heart-wrenchingly personal as well as profound. Very different in subject but equally profound, seasoned journalist and theologian, Wiradjuri man Stan Grant’s Murriyang is his most personal and theological work yet: a memoir of his dad, a biblical lament poem for the darkness of Australia’s history, as well as a meditation on God, memory and time, exploring Christian spirituality in a way that does not shy away from any of the traumas of the past but embraces God with an unashamedly Wiradjuri consciousness. Alan Noble’s On Getting Out of Bed is also a wondrously honest and surprisingly hopeful book. Essentially asking the same question that Camus began The Myth of Sisyphus with – why should you go in living when you feel crushing depression and despair at life? – he arrives at a uniquely Christian answer that offers no trite platitudes but ultimately affirms the value of living despite everything.

In graphic novels, there were not as many highlights as in previous years. I adored Gina Siciliano’s biography of Renaissance artist Artemisia Gentileschi, I Know What I Am, a confronting but inspiring story of an extraordinary and resilient woman, filled with Siciliano’s evocative renderings of Gentileschi’s art. Una’s Becoming Unbecoming, a gritty examination of the author’s own experiences of gender-based violence against the chilling backdrop of the Yorkshire Ripper murders, was unflinching yet sensitive in how it presented its challenging and highly important subject. The Emotional Load, French cartoonist Emma’s follow-up to The Mental Load, was not as life-changing for me as her first (see last year’s reading recap for that one), but it was still powerful in its simple but evocative illustrations and matter-of-fact storytelling.

Two honourable mentions need to be given to 2025 releases of new books by literary veterans. Anne Tyler’s latest novel, Three Days in June, isn’t the late career masterpiece that Redhead by the Side of The Road and French Braid were, but it has all the hallmarks of Tyler’s Baltimore universe, and the same compassionate and unsentimental portrayals of its flawed characters, while developing a narrative voice that is at once distinctly Tyler while also feeling new. Besides, any new Tyler is worth reading because it might be her last. The same can be said of Luci Shaw, whose An Incremental Life sadly did turn out to be her last, with the legend of Christian poetry dying late this year at 95. It’s a wonderful final work in a glorious career, with touchingly raw and tender renderings of old age and the fullness of a life of love lived before God. And which poet doesn’t quite to be still writing like Shaw was at 95? See you in glory, LS. You made contemporary spiritual poetry seem possible and like something I wanted to create.

It turns out that reading books properly is far more fulfilling than pretending to read them. But I still have fifty books on my TBR list and another ten that I’m currently reading, so it’s time to get cracking on my reading for 2026.