Some recent conversations with friends, along with a handful of other influences – skimming, for instance, the last book of essays published by the late Peter Steel, then picking up his last book of poems just today – have got me thinking about poetic form, about the vast range of forms out there which have kept poetry vital and inventive for a long time, many of which are largely neglected by contemporary poets. Why is this? When T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound used free verse, it was a social statement, a rejection of an artistic order which no longer reflected the fragmentation of post-war reality. But even Eliot, after his conversion to Christianity, began to write more ordered, traditional poetry; and many today are starting to see that, if all we have is fragmentation, life is not much fun and does not make terribly much sense. Perhaps we are starting to see that form is not all that bad; perhaps we can see that form, in its place, can be helpful.

At the very least, I have been thinking increasingly about the value in form as a means of both creative challenge and artistic discipline. Working in a variety of forms forces me to improve as a writer, to increase my versatility, much in the way that an athlete works on their strength, fitness and flexibility and a musician works on their range.

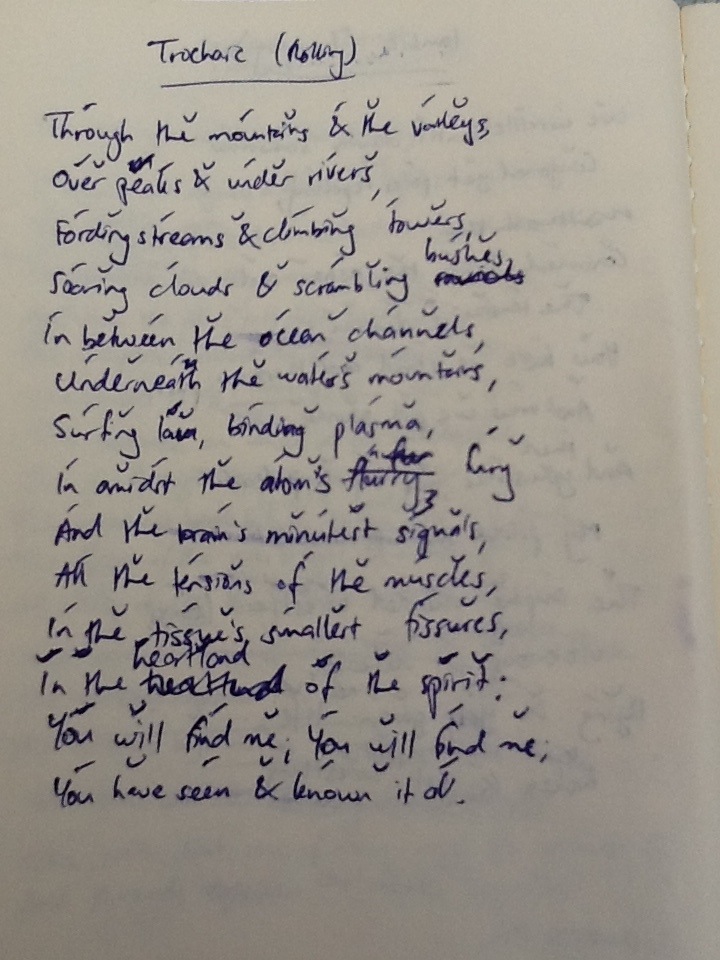

And so you can expect to see me posting here some experiments with different poetic forms, both structurally and rhythmically. Today’s experiment is rhythmic. There are four types of poetic “feet” that can be used, and I am going to practise writing in each one, to see both how it is done and what effect it has.

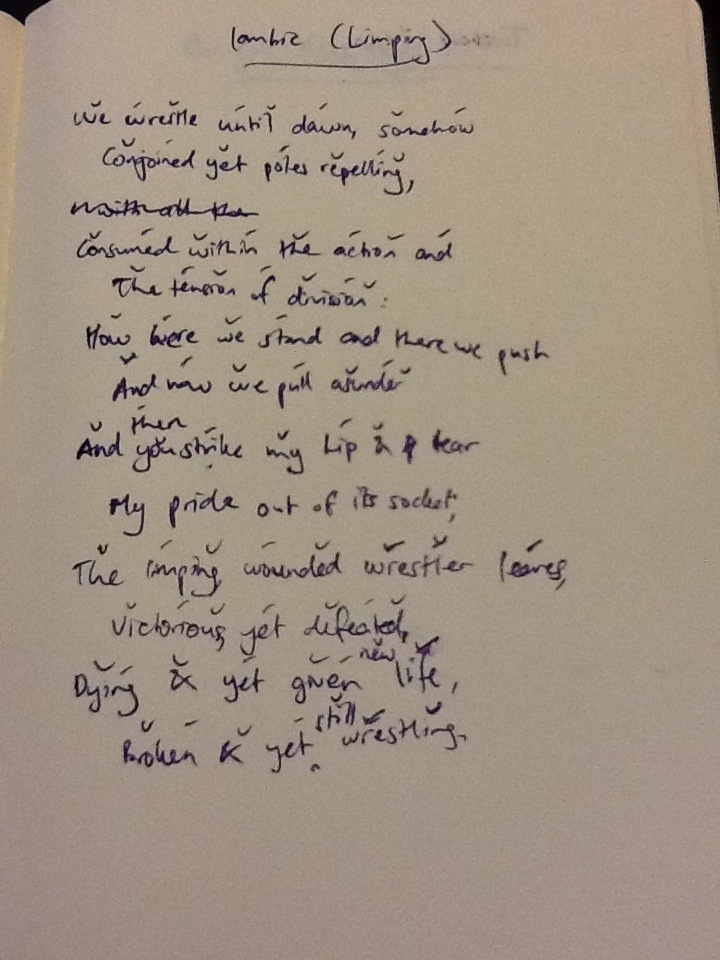

My first experiment is in the most famous and, for me, the most familiar and comfortable of the feet – the iambic foot. “Iambic” actually means “limping”, and so I am playing with that idea in this poem. At its best, form always complements meaning, so today’s poem is a slightly literal investigation into how that works.

Limping

We wrestle until dawn, somehow

Conjoined yet poles repelling,

Consumed within the action and

The tension of division:

How here we stand and there we push

And now we pull asunder,

And then you strike my hip and tear

My pride out of its socket;

The limping, wounded wrestler leaves,

Victorious, yet defeated,

Dying, and yet given new life,

Broken and yet still wrestling.

I am including here the handwritten version of the poem for those interested in seeing the creative process. The symbols above the words indicate the unstressed beats (breve, indicated with a loop) and the stressed beats (indicated with an accent).

-37.792707

144.928056