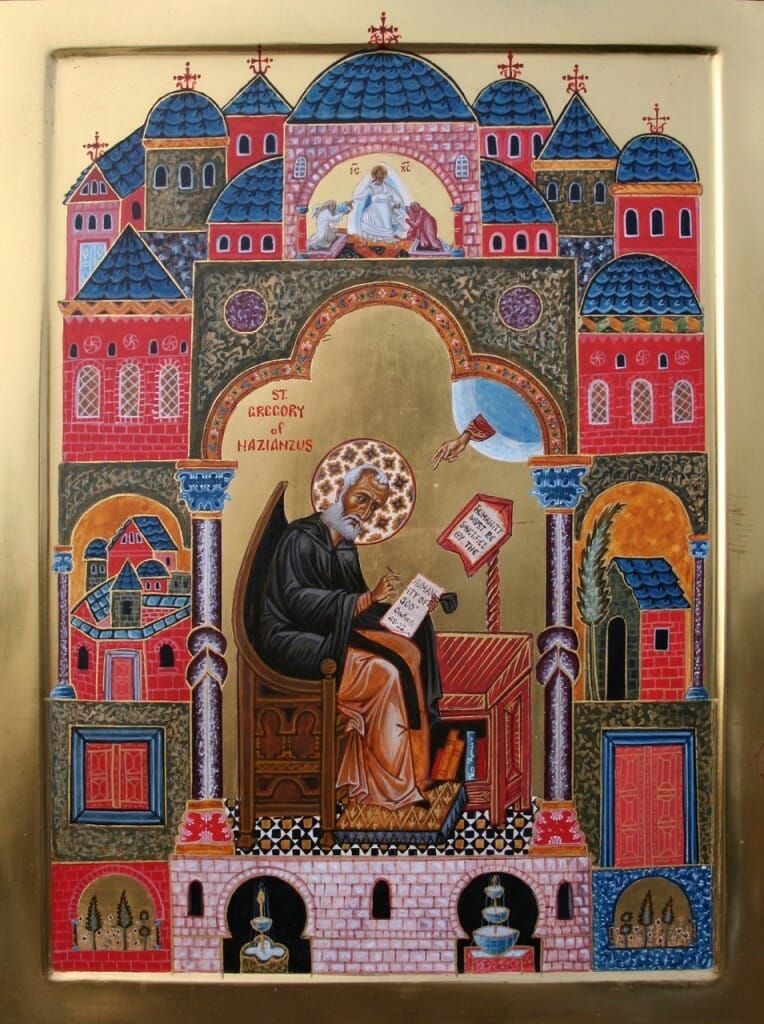

Fittingly, after yesterday reminded us that Jesus was – and is – fully God and fully human, today we remember one of the early church leaders who did much to ensure the church held on to that truth. January 2 in the western church calendar remembers two of the Cappadocian Fathers, Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus. Gregory, a theologian and poet, is famous for leading the Council of Constantinople that developed the Nicene Creed, as well as formulating a lot of the language that the church today uses to talk about the Trinity and the divinity of Christ.

Yesterday we saw how people have always struggled to come to terms with Jesus’ divinity and his humanity being in complete union. One of the particular challenges to this idea in Gregory’s day was the teaching that Jesus had a human body but not a human mind. Now, this is a particular distinction that may not make much sense to us today, because so much of what we think about the “mind” is now captured in our ideas of the brain, and they really can’t be separated from the body. But in the ancient world, even in the early modern world, mind and body were commonly split in people’s anthropology, and it says much about this particular worldview that it struggled to conceive of God having a human mind.

That said, I think we often fall into a bit of a mind-body split in the church today. The purity culture of 1990s Evangelicalism that I grew up with talked about your “thought life” and we often struggled to have a pure “mind”. While watching your thoughts is an important part of discipleship, it can’t be separated from our bodies. Try thinking clearly, or purely for that matter, when you’re tired and hungry, and then try again after a good night’s sleep and a healthy meal, and you’ll see what I mean.

The good news, Gregory of Nazianzus says to both his day and ours, is that if Jesus has both a human body and a human mind, he saves all of us. In fact, making a point more commonly found in Orthodox theology, all of us can be “assumed” into God (unified into God) because Jesus has taken on all of our humanity. We are not just saved bodies with our minds left unsaved; we are saved to the uttermost, even our minds or, as we might say today, our neural pathways.

It also says that the innermost, private part of ourselves – our hidden thoughts – are not cut off from God, as though our bodies carried out an appearance of salvation but our minds kept the truth secret. No, Jesus with his human mind has the power to save the most hidden recesses of our minds.

As someone who has struggled with mental illness for most of my life, for whom the often dark world of my thoughts can feel furthest from salvation, I am greatly comforted by this aspect of Jesus’ saving work and incarnation that Gregory of Nazianzus preserved. And I hope you are too.