Some hands hold their stories tight;

others hold them open, to say,

Here I came when the war was done,

or, Here I lost my mother.

Hands cupped like hearts line the street;

stories filling houses beat.

Old street names speak of sheaves of wheat;

some go out weeping, some sing,

some, sleeping,

dream of other homes, or these,

and best and worst all suburbs breathe

and hearts still beat Your name, although

in early autumn dust we seldom

stop to hear, to praise.

Wednesday’s Colours (Glenroy Lent #2)

Fire is the colour of the eastbound sun

lighting the face of the dusty sky.

Ash is the colour of this roadwork black,

of tarmac where the plane lost flight.

Red is the colour of the traffic light,

gold the colour in the new day’s eye,

and ash to ash is this road we drive;

no dust be lost today.

Glenroy Lent: Long Shrift

Suburb has its own time.

Nestled just beneath city’s scheduled view, it sits

when city runs. It holds

deep memories and secrets, left

in garages, holds hopes

in council offices. Roadwork

punctuates the day’s first lines.

Promises in orange signs declare:

something soon is happening. Prepare.

You may have left your lunch behind, may have left

the drive too little space to breathe.

Watch out for traffic. Slow the start

in day’s suburban street.

Slow the beat of self-knowledge,

slow the heart to blink awake.

In Transit

…lucky to be leafless:

Deciduous reminder to let go.

(Eugene Peterson, “Blessed are the poor in spirit”)

Lost in auto-pilot, I find myself,

false turn on false turn, circling in

this airport country where lanes diverge to let

the suitcase-laden taxi-bound

find ways to cities, and ways away.

A loop, and again I am where

I more or less should be: a road.

Yet airport, out of place, lingers in memory,

and just above

the warehouse-horizon hovers

a plane, a reminder, lest

in all my circling I forget.

Trucks are bound where their cargo is bound;

my cargo’s built for no road,

only sky. And so this day,

let transit pierce the veil;

amidst all of this,

drive praise.

“The thick darkness where God was”

This is what must first be given to the painting, a harmonious warmth, an abyss into which the eye sinks, a voiceless germination…

(Paul Cézanne)

How often is he shown with those horns of light,

as though his head were itself full

of the brightest luminescence and

two cracks, two holes

had formed inside his skull to let

escape all that light, kept

invisibly, impossibly, inside.

Yet for Rembrandt see

how darkness grabs the eye much more

than all the plainness of that face,

how even those two tablets seem

as black as all the dark to which

we’re told that he drew near, while all

of Israel stood just far enough

away to not be safe.

And when El Greco takes

the striking forms of Sinai as

his text, the darkness is

in every shadow-line beneath

the redness of the clouds, around

those rocky pillars, rising from

the chalky, sketchy ground.

Not darkness, but light, shone forth

from those two tablets when

the light-horned Moses brought them down.

Yet light like that we must squint to see.

When fear declares that only man

is safe, that we can’t bear to hear

the voice that struck the tablets’ side:

O let us step, like Moses, to

that darkness without human horns

where only in that absence

of human sight can all Your light

be ever fully seen.

“You are God’s field, God’s building”

Good news.

He also works in earthy things:

not only stars but soil and grass,

carves churches from stone souls,

makes mud-houses whole, and knows

the ways a seed must break. Good news

that maimed bodies are his building,

that the one-eyed, the lame,

may be fed in his field,

good news that his

is the one needful Whole.

Open your sin-severed eyes.

Epiphany brighter than day is here,

bringing harvest,

ripening barns-full of all His toil.

“A catholic taste,” she said

and I nodded,

not knowing at all what she meant, for I

was not, nor have ever been, Catholic.

How then, I wondered, was my reading taste catholic?

The word, at the time, meant Mary and popes,

not expansive, far-reaching, inclusive. Now I

give my old teacher’s words new meaning:

yes, catholic in reading, in writing, because

bodies matter, and ritual

and beauty are core;

catholic because

bread and wine, and brokenness,

sacrament, liturgy,

should inhabit the fibre of the Christian page.

Faith is not, should never be, prose.

So Mauriac and Merton, Marion and Nouwen

shall show me the way to paint Christ

in rich praise.

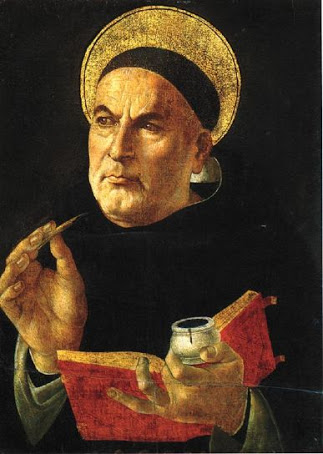

“With pen in hand”

The fact that a work of such unperturbed objectivity and such deep, radiating peace could grow from a life which, far from being untroubled, consumed itself in strife, gives us an insight into the special quality of the man.

(Josef Pieper, The Silence of St Thomas)

The branch is not the root system.

When you see the grandness of the oak,

the stateur of the pine, the fir, do you

also know the deep

tangling that grows beneath?

And rhizomes too

defy our linear longings

to simply be a trunk, a branch.

They entwine, enfold, arise in grace, out of abyss,

of mire.

Aquinas, it is said, was never

led by spirit but by thought.

“He contemplates…with pen in hand”*,

as though the pen were like a fence-post

constraining the grace of higher thought.

When, twenty-three, I took graceless aim

at shots fired over tea against my faith,

my sparring partner only said,

You know what you remind me of?

The scholastic period. The scholastics, man.

An insult? Perhaps. I did not speak

of the nights I’d spent in faithless fear.

All I am, and was, is straw. Yet pen

takes roots beneath the page,

and rhizomes grow within the nib.

Only grace that minds can ever take wings;

grace that pens can gather thought.

All grace that straw can speak.

*Adrienne von Speyr, The Book of All Saints

Advance

We also came across the seas, my people:

Romans, Vikings, colonials, the lot of them,

convicts and scoundrels, emperors and ne’er-do-wells.

They came and they saw, they usurped, or were sent.

You came like us, to this lucky country.

You came in hope. We take it from you.

We also heard of the boundless plains;

we, my people, did not like to share.

Advancing ourselves, your foul was our fair.

Fences excluded; excluding, we fenced.

Tall hedges, tall stories: we made our own glories.

You came here for freedom; we came to rule.

I do not recall the home we came from.

You carry yours as a scar, and the ones

before us both know every hill’s name.

I must steal this to call it my own;

I squander what never was mine, and you look

through bars at the freedom we feast on. Our hearts

are never at home.

Resolution: No Clutter

Too fidgety the mind’s compass

(R.S. Thomas, “Adam Tempted”)

I pile books on books and

thought on thought. I pile

obligation onto guilt, and duty

onto resignation. This

is panic in my breath and limbs

tingling with the pace of things.

There is no end, the wise teacher said,

to all flesh-weariness of thought.

I must find instead a small

pocket of my father’s grace;

I must breathe and breathe and breathe

in pinpoints where His kindness rests.

Not absent, Lord – You have never been

on holiday; You, O God, don’t sleep.

Yet in Your weekly scheme is space;

all Your bookshelves mouth Your peace.

Not absent, Lord. It is I who have been

too busy with my piles and piles

of nothing. You are everything.