If it had roots, the pulling-out would be easy,

but, being rhizome, it tangles its way far, far out,

as though sending emissaries, ambassadors;

but which way do they travel?

Do they depart or return?

The beginning hides sneekily under soil,

like a power-line, a waterpipe,

some subterranean transport network,

while the visible growth bursts

somewhere else,

a periscope greeting, a hand waving to the day.

Like me, it craves light and craves soil.

Hence this tangled network, this clump

of green and brown, like a jungle, like a weed.

If it had roots, the pulling-out would be easy.

Not so the rhizome; it is too much like me.

In Translation

If you find them worth publishing, you have my permission to do so – as a sort of ‘White Book’ concerning my negotiations with myself – and with God.

(Dag Hammarskjöld, in a letter to Leif Belfrage)*

And so they sat together, the poet

without “a single word of Swedish” at hand,

and the translator, to find together –

to trace – the private markings of the public soul,

the one to give the language, the other the heart,

the rhythm, that “unexpressed dialogue”

without which language dies.

And what did they find, as

layers fell and layers grew?

A planned self-defence? The last

word to silence posthumous debate?

No, the heart’s x-ray more like it;

a confession; a line drawn around

the self’s ever-moving hand.

He knew no Swedish, but Auden at least

knew that movement well: the soul’s

duplex structure; the twin-tangle of light and dark

that makes the mess called Man.

The redemption too; he knew that as well.

The call, the answer: the Whitsunday “Yes”.

This too is in the soul’s true language,

spoken best in the gap between

thought and speech, seen best when glimpsed

eyes squinted open to light,

half-closed to self, half-

forgetting all we thought we knew.

In translation,

the soul is seen translating,

atom-swift. Catch it

as it propels to break new ground.

* Before his death, UN secretary general Dag Hammarskjöld left his journals to his friend and fellow diplomat Leif Belfrage. Poet W.H. Auden worked with Swedish writer and translator Leif Sjöberg to translate this diary into English. It was published under the English name “Markings”.

What we don’t know

It is hard for those who live near a Bank

To doubt the security of their money.

T.S. Eliot

Only those who have felt the cold

will remember to close the door.

Only those who are fallen or proud

will perceive the rule of law.

Only those who live far from the bowl

will know it means to need more.

Only those who believe they might win

will bother to check the score.

No Ordinary Sundays

Before you lies my strength and my weakness; preserve the one, heal the other. Before you lies my knowledge and my ignorance; where you have opened to me, receive me as I come in; where you have shut to me, open to me as I knock. Let me remember you, let me understand you, let me love you. Increase these things in me until you refashion me entirely.

Saint Augustine of Hippo, The Trinity

We do not call these Sundays ordinary:

transfigured by revelation, by mystery,

they stand apart.

By these days we set

our calendars, and, in the old days, we said,

In Hilary term, or, Before Trinity.

Order is set by extraordinary.

Order in all things,

and yet, in all ordinary things –

some unexceptional people gathered,

music played, some prayers prayed,

some words spoken, some soon forgotten –

extraordinary creeps in, is always the silent witness.

What Augustine knew, we often forget:

community right at Godhead’s heart,

found, reflected, in our meagre parts,

a knowledge too rich for understanding,

coming, and standing,

where we stand. O hold us now;

for nothing else

makes sense unless You remake us.

Uncovered Gems #5: The Danish Psalmist

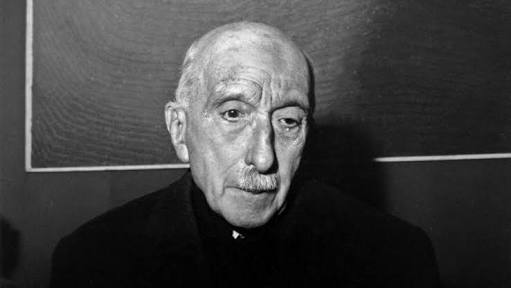

In the Danish Golden Age of literature and philosophy, there were three significant names that still stand out today: Hans Christian Andersen, Søren Kierkegaard and N.F.S. Grundtvig. The non-Danish world has very much heard of the first two but the third is as unknown as it is unpronounceable.

And perhaps understandably so. He is of much greater importance at home than overseas. Grundtvig (pronounced Groont-vi) had a significant impact on Danish nationalism and education, and his role in the Danish Lutheran church was profound. But outside Denmark he doesn’t seem so have had much impact. Nor is he particularly the kind of figure to easily win fans a century and a half after his death. With his formidable muttonchops, Lutheran clerical ruff and an almost permanently austere look on his face, Grundtvig does not exactly appear to be one to welcome 21st-century popularity. My first encounter with him was when ultra-right party leader Svend Åge Saltum quoted him in Danish political drama Borgen. Yet there is much more to Nicolaj Frederik Severin than austerity and Danish nationalism. Basically, imagine English church life without John Newton or the Wesleys and that would be the Danish church without Grundtvig. And the comparison’s a fair one, at least when it comes to his hymns, because it turns out that one way in which Grundtvig is kept alive and well is in Danish worship.

My first proper encounter with the 19th-century poet, pastor, philosopher and translator was in the music of Danish band Kloster who set a whole bunch of his hymns to some gorgeous, otherworldly tunes on their album Ni Salmer og en Aftensang (Nine Psalms and an Evening Song). The track that first arrested me was the magically tender “Urolige Hjerte“, with its gently thrumming guitars and the opening words:

Restless heart, what ails you?

Why are you in pain?

Is there anything you need?

Is He not your father who has your everything?

And aren’t all my thoughts and hairs numbered by Him?

And hasn’t He chosen me to be His best friend?

Urolige hjerte!

Hvad fejler dig dog?

Hvi gør du dig smerte,

du ej har behov?

Er han ej min Fader, som råder for alt?

Er ej mine tanker og hovedhår talt,

og har ej den bedste til ven mig udvalgt?

Sadly, lack of interest in Grundtvig’s poetry means that almost none of it is available easily in English – a little ironic for a man who translated one of the most significant English poems, Beowulf, back into the language that inspired it. There is one substantial collection of his poems in English but it’s expensive and not easily available. So, if I want to listen to his songs – which I do – and want to understand them too, then I have to try translating them myself.

It’s a wonderful experience, reverse-engineering a Grundtvig poem into English. Translating poetry is hard in any situation, harder still when your grasp of the source language requires a fair bit of Google Translate to get anywhere beyond, “The polar bear is drinking beer” and all those other useful phases Duolingo teaches. But, slow-going and humbling as it is, I feel closer to Grundtvig’s work for doing it. I have to marvel at the tautness of his metaphors, the subtlety of his rhymes – so hard to replicate in English, when we don’t have one word that could mean both bleed or fade that also rhymes with “regions” or “areas”. And I am struck by the deft way he melds Biblical text with the immediacy of everyday life. Take the hymn that I’m crawling through at the moment, “En Liden Stund” (“A Little While”). The hymn takes its title, and the first line of each stanza, from Jesus’ words to the disciples in John 16:16 – “A little while and you will see me no longer…” But Grundtvig takes Jesus’ words and first looks at something that is beautiful and impermanent, a reminder of how our lives look next to eternity. There’s no translation that can fully capture what he says with the first lines, at least not without losing the rhyme:

A little while

in roses’ grove,

we only blush and fade…

En liden stund

I rosens lund

Vi rødmer kun og blegne…

For a man who looks most likely to either preach brimstone or thump the bar to ask where his Carlsberg is, there’s remarkable tenderness and pastoral heart in Grundtvig’s words, not to mention a sense of pure beauty. Like most nineteenth-century poets there’s some inverted sentences worked to fit in rhymes that sound sometimes cumbersome to our ears today. But his love for God and God’s people is fresh and alive. Not surprisingly; much as Kierkegaard laid into him in his final polemic days (Grundtvig, wisely, had less to say about Kierkegaard), they wanted the same thing: to see the dry bones of the state church animated with living faith. Fittingly, Grundtvig loved to sing about new life in Christ, whether symbolised in Christmas or Easter or the day of the Resurrection. So here is a lovely translation by S.A.J. Bradley of one of his poems on this theme:

1. Ring out, O bells, oh ring out while the world yet lies darkling;

shimmer, O stars, like the light in the angel-eyes sparkling.

Peace comes to earth,

peace from God through his Word’s birth:

– Glory to God in the highest!

2. Christmas is come as a solstice to hearts that were fearful!

Christmas and Child, son of God, where the angels sing cheerful,

all is God’s gift,

bidding us our hearts uplift:

– Glory to God in the highest!

3. Children of earth clap your hands and come dancing and singing,

raise up your voices till earth’s furthest corners are ringing.

Born is the Child

of the Father’s mercy mild:

– Glory to God in the highest!

Winter Song

Write me

a poem like the early spring, pluck

me a chord like a green flower-stem.

Open the dance where we know all the steps

to these known tunes that never will end.

Weave me

a curtain to let in the light. Cast

me a rainbow without any dye.

Spin me a question without an exam

and sit open beneath this expanse.

Twinkle

a star for me up in the sky. Grant

me a Balaam to thwart and reply.

Sing me a lyre that can silence a Saul.

Spring me a poem that will never upend.

Pray me a bottomless ever Amen.

Uncovered Gems #4: François Mauriac

The list of Nobel laureates for Literature contains more French men than it does of any other demographic. That should not put you off reading Mauriac. But you may have trouble locating his work. His most famous novel, Thérèse Desqueyroux, is possibly the only one you’ll find in a bookshop today, due to the recent film adaptation starring Audrey Tatou. And it’s a good place to start with Mauriac.

Better than good. Aside from the beauty of the writing and its complex vision of sin and grace, it’s an important novel for understanding him as an author. The character of Thérèse also features in a number of novels and stories, and even has a cameo in That Which Was Lost, so she clearly meant a lot to him.

But there’s more to Mauriac than one novel, and you’ll need to go further afield to find out. It’s a strange fact that most Nobel laureates are not readily available in bookshops. But the internet was invented for solving issues like these. The majority of Mauriac’s novels are free downloads if you are willing to read facsimiles of old editions. And you should be, because not many Christian writes have tackled human sin and divine grace quite so skillfully as Mauriac. He’s sometimes called the French Graham Greene. There’s some truth to the comparison but I don’t think Mauriac liked the crime thriller quite like Greene did, and I find more living faith and less guilt in Mauriac. The closest thing I’ve found in English to his writing is Brideshead Revisited. Both show people living in complete disregard for God and discovering Him in completely unexpected ways nonetheless.

Some writers of faith get reprinted and sold at Christian bookshops, even when faith is not their main subject. Chesterton and Austen have both had fairly secular novels get the Christian marketing treatment. Not Mauriac, and I can see why. His faith is more overt than Austen’s but will make us more uncomfortable. (Perhaps Austen would too if we read her properly.) He doesn’t shy away from broken and messy realities, and even had to write a book called God and Mammon responding to André Gide (another French man who won the Nobel) who saw more kinship between himself and Mauriac than Mauriac was happy to accept. His work is gritty in a way that can’t sit next to Christian romance novels, but it should. Our shelves, and our faith, would be richer for it.

For me, the best thing he’s written is Viper’s Tangle, the story of a wealthy man dying with the knowledge that his whole family cares only about securing his wealth on his death. The viper’s tangle of the title is the complex rhizome of bitterness and resentment that has grown in his heart and mind all his adult life. I read it at the same time as Tolstoy’s Death of Ivan Illyich and the two have much in common. Both made me wonder why we don’t have more Christian writers who can dramatise the movements of grace like that. Sadly, in our attempts to keep Christian literature clean, we’ve kept the power of grace out. Christian fiction does not need to be an allegory of the gospel to paint the gospel in all the rich colours of God’s creation. If more of our writes today took the time to uncover Mauriac, we might produce more novels that could help untangle the vipers in our own hearts.

Uncovered Gems #3: “The Singer” by Calvin Miller

“How did you manage to make them cherish all this nothingness?” he asked the World Hater.

“I simply make them feel embarrassed to admit that they are incomplete. A man would rather close his eyes than see himself as your Father-Spirit does. I teach them to exalt their emptiness and thus preserve the dignity of man.”

“They need the dignity of God “

“You tell them that. I sell a cheaper product.”

When Dr Calvin Miller – pastor, author, poet and evangelist – died in 2012, Ed Stetzer said of him in Christianity Today that “Dr. Miller knew the importance of story as well [as evangelism]. A wonderful wordsmith, he would use the element of story in such a way that cold facts and dry doctrine came to life in ways rarely seen”. Poet Luci Shaw, one of the only really talented evangelical poets I’ve come across, said in his lifetime that “Calvin Miller sees with a single eye”, producing literature “full of light”.

His prose poem The Singer may be a little too much of its time (the 1970s) to earn many readers easily today, yet, stumbling on it in the painfully small Literature section of my theological college’s library, I can see the qualities that Stetzer and Shaw praised.

An extended metaphor on the incarnation and mission of Jesus, The Singer boasts some of the most remarkably pithy lines and phrases that I’ve encountered in 20th-century creative religious writing outside Lewis. The Singer, tasked with singing of God’s good creation and calling a broken world to healing, regularly encounters the World Hater, Satan, whose counterfeit song recalls the two songs of Tolkien’s creation narrative in The Silmarillion. As the two figures of the Hater and the Singer travel to teach their different songs, not all are drawn into the purity and healing of the Singer’s eternal song. Even his mother warns against his singing the final verse “against the wall” of the Great Walled City of the Ancient King:

She cried.

“Leave off the final verse and not upon the wall.”

He kissed her.

“I can’t ignore the Father-Spirit’s call. So I will sing it there, and I will sing it all.”

At times, Miller’s allegory is heavy-handed, as allegory often is. And I wish deeply that evangelical authors could see the value in writing fiction that is not allegory. Yet the merit of Miller’s writing is the way it illuminates more than it retells. Not every detail of his story neatly correlates with a Biblical fact, and much of it is more poetic than doctrinal. But, as Stetzer observed, that’s his strength: seeing the value of story, and bringing back the poetry and power of the story in a way that theology often cannot do.

I for one will be looking for more of what Miller wrote in his rich and grace-driven lifetime.

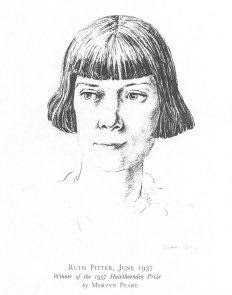

Uncovered Gems #2: Ruth Pitter

Last week I posted a poem in honour of Christina Rossetti, who I declared one of the Anglican church’s greatest literary exports. Today, in this week’s uncovering, I want to share with you the work of a widely forgotten gem, the Anglican poet Ruth Pitter. I have my friend Nathanael to thank for this discovery, a poet who is sometimes known as “the woman who should have married C.S. Lewis” (and who is widely recognised as a better poet than he ever was). She was also the first woman to receive the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry, alongside winning a number of other prestigious awards. And yet few have heard of her today. In fact, I only discovered her because my friend printed out some articles on her for me – and I’m very glad he did.

Pitter is not, perhaps, the sort of poet who will win many fans easily this century. Her verse is determinedly traditional. Her first book of poems (just called First Poems) has more references to fairies than are wholly to my liking (though she means it in the Tolkien or Neil Gaiman sense, not in the vein of Tinkerbell). But most of all, she is hard to get into today because her work is largely unavailable. You have to be willing to do a fair amount of your own work to discover her, and what incentive do you have if you’ve never heard of her?

Well, the purpose of this post is simply to make some of her work a little more readily available to those who are interested. Because, apart from the obstacles in our 21st-century way, Pitter deserves our attention. Her work is delicate, in a way that is both beautiful and illusive. It refuses to be pinned down, yet it is filled so often with a clearly sacramental imagination. For Pitter, the world is fleeting but points to lasting things. Darkness hurts yet is transfigured by day. Relationships are imperfect yet transfixed by irreducible grace.

One of the best clues to Pitter’s work for me came from this interview, in which she distinguishes between two types of obscurity: the “noble” obscurity in which the poem illuminates something unseen or unknown, and the “slovenly” obscurity that detracts from meaning without adding to it. Pitter’s best work feels like crystal-clear water, of a kind that perfectly allows us to see the rich complexities of the rivers’ floor beneath.

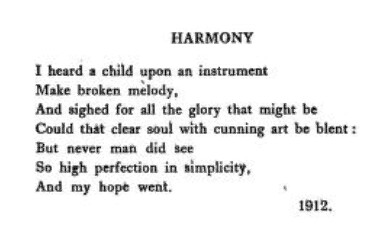

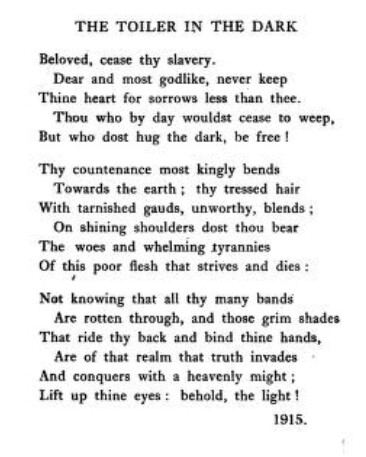

Here are just a few snippets of her work. I’ll let them speak for themselves.

And to finish, here is one of her most joy-filled offerings that I’ve found.

The Plain Facts

See what a charming smile I bring,

Which no one can resist;

For I have found a wondrous thing –

The Fact that I exist.

And I have found another, which

I now proceed to tell.

The world is so sublimely rich

That you exist as well.

Fact One is lovely, so is Two,

But O the best is Three:

The Fact that I can smile at you,

And you can smile at me.

The Language of Flowers: For Christina Rossetti

As an Anglican myself, I have to say that our literary exports don’t get much better than Christina Rossetti. Granted, she’s in formidable company, alongside George Herbert, John Donne, William Cowper, C.S. Lewis, T.S. Eliot and R.S. Thomas (why did you need to have the middle initial S in order to be a successful 20th-century Anglican poet?). Yet Rossetti is special for a bunch of reasons. She stands to this day as one of the most important female writers of her day – no small claim when you think of some of the writers she shared an era with – and has a remarkable balance of spiritual richness and honest as well as transcendental exploration of life that makes her successful not just as a writer of faith but also as a poet. She endured much in her life and produced poetry of only increasing beauty through that life, growing both in honesty and grace as a writer. It’s fitting, therefore, that she has a day in the Church of England calendar in her memory. It isn’t celebrated in the Anglican Church of Australia, but I can’t let a minor feast day for a beloved writer go by without writing something to honour it. So here is a poem in memory of an amazing woman, Anglican and poet.

The Language of Flowers

There it was,

in your garden, amidst

bleeding cyclamen, besides

burdened burdock and a trampled

patch of furze and hyacinth.

Ivy was torn

where you cut through the garden;

juniper drooped and lilac sank.

Yet, then you spied the valley lily

growing where it should not grow,

and a shock of eglantine.

Soft, you thought:

“I planted cyclamen to say,

I must wait. I gathered

burdock with its spines to say,

This is done. So go away.

I am done with artifice;

clematis I will rip from soil.

With dogwood, I am durable.

I cannot plant much else.”

Yet there it stood,

unplanted, unthought. When you went

to pluck a thorn to pierce

a puffed-up dream, you found instead

in varied purple-yellow-white

the heartsease for your sleep, and found

a day-bloom burst from night.

You had ripped

your palace down. There was no place

to lay your head but grass and weed.

Yet on that bed of purple light,

you dropped to rest your heart.